Guest Essay: A Social and Visual Diary of the Northern Ring Road by Guillaume Beaud

Guillaume Beaud

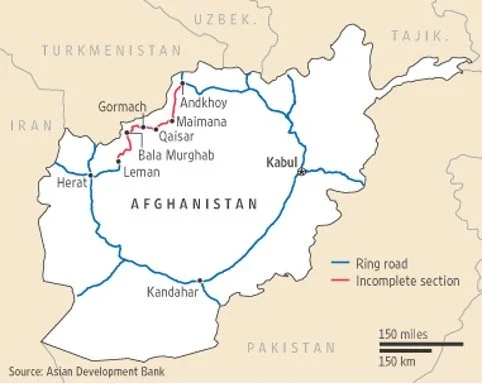

As a landlocked and mountainous country, Afghanistan has long sought to equip itself with road infrastructure to bolster trade, human mobility, security, and regional connectivity. In the developmentalist era of the 1950s and 1960s, King Zahir Shah balanced Soviet, then American assistance to modernize and asphalt what became known as the Afghanistan Ring Road (in Dari, shāhrāh-ye halghavi-ye afghānestān). After decades of war ravaged the country’s road infrastructure and hampered its expansion, road reconstruction became the second-largest aid-recipient sector in post-2001 Afghanistan, with an estimated 4 billion dollars spent between 2001 and 2015, 3 billion on the Ring Road alone [1]. One road portion was never completed, however.

Between the predominantly Uzbek-speaking city of Maimana and Herat, former Timurid capital and cultural heart of Khorasan looking west toward Iran, lies a 233-kilometre stretch, weaving through a modest mountain range along the Murghab river, that was never asphalted, leaving the Ring Road a broken one.

Though hardly accessible, Afghanistan’s north-western road featured prominently in the famous writings and photographs of Swiss travelers Ella Maillard and Anne-Marie Schwarzenbach [2]. It also appeared in the recently acclaimed road-movie documentary Riverboom (2023), in which yet another Swiss writer and journalist Serge Michel engages in a journey along the same route in early post-2001 Afghanistan.

In 2012, a joint American-Turkish venture was awarded 480 million dollars to build the missing section. In his first cabinet meeting in 2014, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani ordered the Ministry of Public Work to complete the ring road within nine months, in the name of regional integration and trade. This never happened. The company started the project but then disappeared without delivering, entering in a legal case against the Afghan government it blamed for failing to provide security, amid evidence that subcontractors and criminal groups siphoned off part of the funds [3]. By 2015 indeed, the provinces of Fariyab and Badghis faced severe security challenges, with Taliban insurgents intermittently controlling stretches of the road [4].

After the Taliban took over the country in August 2021, Afghanistan’s new rulers pledged to rebuild infrastructure to foster domestic mobility and regional trade, as part of a broader performative display of the return of state authority and security. Yet traders and truck drivers still complain about poor road conditions of the un-asphalted section of the Ring Road, leading to rising food prices and frequent accidents [5]. Although road works financed by Saudi funds were recently launched on the southern portion of the route [6], Herat remains largely cut off from the north of the country, Mazar-e Sharif and onward to Uzbekistan and the new Aritom free-trade zone inaugurated in 2024.

Guillaume Beaud

Last July, I embarked on an 18-hour journey along the missing section of the Ring Road. From Maimana depart bumpy, old-style minivans and the famous electric-blue shared taxis known as ‘Corollas’, named after the Toyota model known for its robustness and the availability of spare parts, imported second-hand from Dubai’s used-car market [7]. I ended up in a Corolla with three travelling companions.

Guillaume Beaud

Their lives and journeys along the Ring Road bore the imprint of a turbulent history, fractured family and social ties, and contemporary forms of mobility in post-2021 Afghanistan marked by restored security and increased movement, yet continued economic hardship and pervasive unpredictability.

The first and the most colourful character was a Hazara mullah in his seventies, the son of a farmer from the northern province of Samangan. For three decades, he has been teaching the Qur’an to young Afghan boys in Qom, Iran’s second holiest city and a centre of global Shia scholarship. He had four sons and two daughters: two of his sons died, another lives in Sweden. Accustomed to life on the road between Mazar-e Sharif and Qom, totalling nearly 50 hours in shared taxis and buses, he travels with a simple backpack and a large plastic kettle for tea. He had left Iran a few weeks earlier, following the Israeli bombings of June 2025. Now he was making his way back to Qom, while Iran carried out mass deportations of Afghans, invoking security concerns as a pretext in the wake of Israel-Iran’s 12-day war that bolstered the Iranian government’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. In July alone, 370,000 Afghans were expelled from Iran, 70% of whom arrived through Herat [8]. To war, dislocated family ties, and the uncertainties of politics and road travel, my traveling companion responded with a mischievous and playful temper, at times light-hearted, at others grumpy.

The driver makes another character. Uzbek-speaking, he doesn’t say much during our journey, remaining quiet and solitary. In his thirties, with long, straight hair, he is known as “Khalifa,” a title reserved for experienced men of the road. And indeed, he drives with care and patience, his watchful eye attentive to the broken and unpredictable fabric of the road, and to the voice of his ageing Toyota and its capricious mechanics. With his left hand, he smokes with concentration; with his right, he tunes the car radio while driving. Music flows, as in most taxis under Taliban rule, even in cities. Beneath the rear-view mirror, a small screen connected to a USB stick plays video clips of Tajik female singers with powerful voices. So close, yet so far. Upon arriving in Herat, he will likely sleep for a few hours before setting off again at night, taking new passengers back to Maimana.

Seated to his left was a silent man in his mid-forties, travelling to Tehran, where he has worked for more than twenty years in the construction sector, which employs more than half of Iran’s registered Afghan workers [9]. Under Iran’s temporary work-visa policy, which prevents him from working more than six months a year, his movements are governed by a regime of forced seasonal mobility : every year, he is bound to return to northern Afghanistan to work as a labourer. Not much of a talker, a dark blue-and-green checkered scarf pulled over his hair, he has a taste for photographs, and eats and offers large quantities of Herati grapes from the front seat, for which he paid a small, additional fee to spare himself the jolts of the back seats. The day after our arrival in Herat, he will board a bus to Mashhad, hoping to cross the border without incident, then continue to Tehran, back to the construction site.

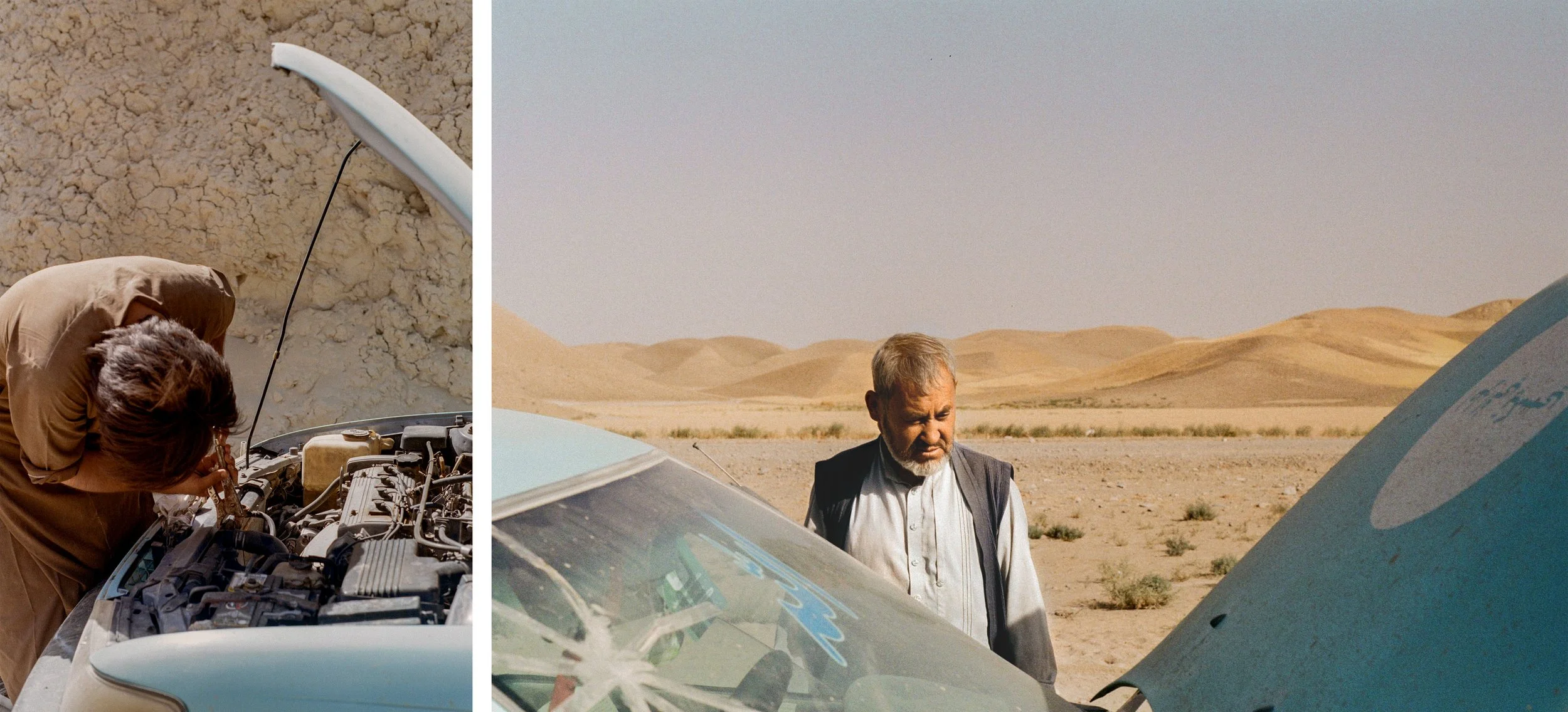

Leaving Maimana, the first two hours offered a pleasant drive on an excellent road, winding through dry hills. Everything seemed promising. The driver remarked on his neighbour’s silence, who pulled out his passport to reveal a colourful patchwork of Iranian visas and stamps, leaving him visibly impressed. As we moved from the province of Faryab to that of Badghis, the fine stretch of asphalt suddenly gave way to a rough, uneven, and loosely traced track along a riverbed. Drivers are compelled to improvise their routes and river crossings, reading the ground for traces of earlier passage, all while avoiding the deepest ruts carved by intense passage. As we left the riverbed to cut through the mountains, Khalifa started stopping regularly to assist cars, trucks, and even tractors facing mechanical failure. He did so out of duty. Such is the moral economy of the road, one from which we would, a few hours later, benefit greatly.

We stopped in the oasis town of Bala-ye Murghab, nestled in the irrigated agrarian valley of the Murghab River, which runs north toward Turkmenistan only a few kilometres further, carving its restless course through the hollow of the dry, mountainous steppe. We then plunged into the heart of the Badghis mountains along a chaotic, sandy track, sealed inside our metal shell burning under the sun. The engine overheated, lurched, and broke down a dozen times over the ten hours that followed, particularly as we crossed and overtook trucks struggling to force their way through, grinding under the weight of goods hauled with great difficulty. Breakdowns multiplied. Help came time and again. Khalifa carefully applied glue to seal the leaking and burning cooling hose, handling tools with the ease and patience of long familiarity. One of his acquaintances followed close behind in his overloaded mini-van, keeping watch.

Guillaume Beaud

We passed many Kochi nomads, Pashtun pastoralists displaced in the late 19th century as part of Emir Abdur Rahman Khan’s centralist project of demographic engineering designed to tighten control over remote provinces. In past decades, land disputes have fueled tensions between ethnic groups. UNHCR tents line the roadside. Wild pistachio trees watch us from the ridgelines. Their fruits will be sorted in the intimate caravanserais–discreet inner courtyards enclosed within the bazaars–of the region’s markets,then sold at a high price across the country, in Kabul, and eventually exported. The heat forced us to drive with windows wide open. Yet every maneuver flooded the car with sand, blinding us and leaving us to breathe through our mouths, teeth clenched on our scarves. We veered onto alternative tracks. Somewhere, surely, roadworks were underway, as evidenced by the motionless tractors we passed.

Guillaume Beaud

After fifteen hours on the road, we reach Qala-ye Naw, a sizable town still bearing the scars of war. From there, the road is gradually taking shape, with intermittent stretches of asphalt. The Taliban have recently commissioned works to ease road mobility around the Sabzak pass, perched at 2,500 meters altitude amid pine trees, leading down toward Herat, where we slipped in the night to the sound of loud Tajik music.

Source: Google Maps

Guillaume Beaud is a French scholar trained in Political Sociology and Persian, interested in bureaucracy and taxation, currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford.

❋

Notes, References, & Sources

[1] Qayoom Suroush, “Going in Circles: The never-ending story of Afghanistan’s unfinished Ring Road”, Afghanistan Analysts Network, 16 January 2015. https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/economy-development-environment/going-in-circles-the-never-ending-story-of-afghanistans-unfinished-ring-road/

[2] Ella Maillard (2022, 1st Ed. 1947), The Cruel Way: Switzerland to Afghanistan in a Ford, 1939, University of Chicago Press ; Anne-Marie Schwarzenbach (2019, posthumous), All the Roads Are Open, Seagull Books [translated from the French edition, 2002, Payot]. For the 75th anniversary of Anne-Marie Schwarzenbach’s tragic death in 1942, the Swiss Literary Archives made freely accessible over 3000 of her photographs, including in the provinces of Badghis, Faryab, and Herat, accessible on https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:CH-NB-Annemarie_Schwarzenbach

[3] “Kolāhbordāri-ye 107 milyon dolāri-ye sherkat-e Amrikāyi-Torki dar Afghānestān” [“The 107-million-dollar fraud of an American-Turkish company in Afghanistan”], BBC Farsi, 11 September 2024. https://www.bbc.com/persian/afghanistan/2014/09/140911_k04_afg_street_project_mopw

[4] See especially Ali Obaid, “Security Forces Spread Thin: An update from contested Faryab province”, Afghanistan Analysts Network, 11 June 2014. https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/security-forces-spread-thin-an-update-from-contested-faryab-province/ In 2009, blogs of foreign travellers already indicated that local officials prevented Westerners to go past Maimana because of Taliban-related security threats. See for instance “The Road to Maimana”, The Velvet Rocket, 18 October 2009. https://thevelvetrocket.com/2009/10/18/the-road-to-maimana/.

[5] “Traders, drivers lament bad condition of Maimana-Herat road”, Pajhwok Afghan News, 7 April 2022. https://pajhwok.com/2022/04/07/traders-drivers-lament-bad-condition-of-maimana-herat-road/

[6] “Badghis Section of Afghanistan’s Ring Road Nears Completion”, TOLO News, 29 November 2025. https://tolonews.com/afghanistan-196797

[7] A second-hand cars as objects of transnational economies in the global south, see the research project funded by the French Research Agency (ANR) “Global Cars : a transnational urban research on vehicle informal economies (Europe, Africa and South America” (https://anr.fr/Project-ANR-20-CE41-0012). On the second-hand car market between Dubai, Central and South Asia, see the work of Gayatri Jai Singh Rathore.

[8] By December 2025, almost 1,2 million Afghans were deported from Iran in the previous year. A large portion were documented. See the latest report released the UNHCR, “Iran-Afghanistan - Returns Emergency Response #26”, 29 November 2025. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/119948

[9] By 2025, an estimated five million Afghans were thought to be living in Iran. On the Afghans in Iran, with an emphasis on the role of mobility in the construction of the self and community, see Fariba Adelkhah and Zuzanna Olszewska (2007), “The Iranian Afghans”, 40 (2), p. 135-165 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/4311887), and Alessandro Monsutti (2007), “Migration as a Rite of Passage: Young Afghans Building Masculinity and Adulthood in Iran”, Iranian Studies, 40 (2), p. 167-185 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/4311888).