Afghan War Rugs: A Material Witness of Occupation

From nomadic craft to global commodity, Afghan war rugs, or qalin-e jangi in Dari, first emerged following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan 1979, a Cold War intervention gone awry that saw the birth of this distinct rug form. Initially produced as novel commodities for Western collectors, over the course of their production, war rugs evolved into witnesses and a historical record of imperial occupation and Afghan resistance.

Rooted in nomadic and semi-nomadic textile traditions, war rugs were primarily produced by the Baloch, Hazara, and Turkmen peoples. As war and displacement began to dismantle traditional livelihoods, people from non-weaving backgrounds took up the craft, often out of economic necessity. Scholars suggest that the earliest war rugs were made by Baloch weavers in northern Afghanistan shortly after the Soviet invasion in 1979.

During the ensuing decade-long conflict, millions of Afghans fled to neighboring Pakistan and Iran. Refugee camps became key production sites where styles merged and knowledge was shared and circulated. In these provisional spaces, even men, who traditionally do not weave, were taught the craft. Production later expanded to urban centers like Kabul, especially after the US invasion in 2001, and became more standardized as dealers supplied design templates to meet a revived market demand. This new wave of commercialization led to a significant rise in production, though many new pieces sold under the label of “war rug” were in fact reproductions of existing carpets and often produced using child labor.

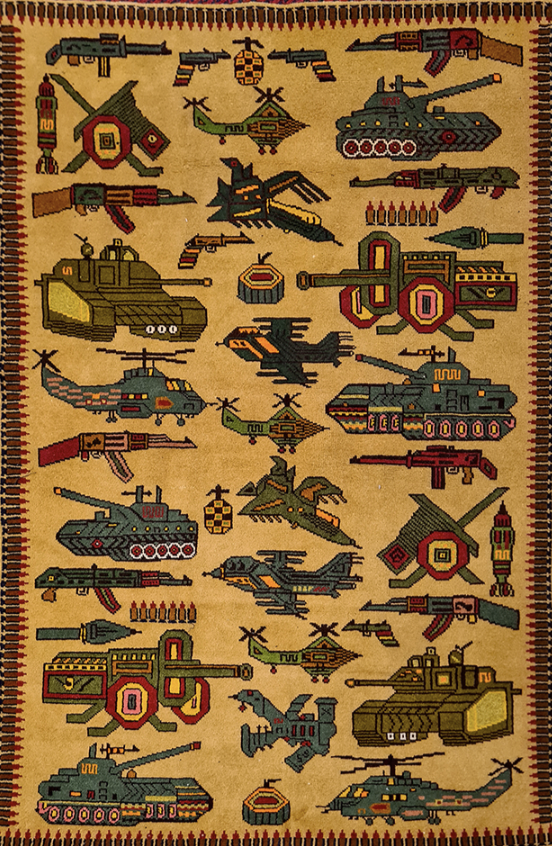

War rugs vary enormously in size, design, technique, and quality of workmanship. One defining feature is how traditional motifs are adapted into military imagery. Flower motifs such as paisleys may initially seem decorative and benign, but upon closer inspection, morph into grenades. Floral forms suggest explosions and Turkmen gul motifs are reimagined as tanks or tank treads. Early examples are more subtle and abstract, while many later examples are densely packed with explicit imagery of weaponry, with the Soviet Kalashnikov rifle and U.S. F-16's featuring prominently. Additional compositions include landscapes, all-over patterns, portraits of political leaders, maps, and occasionally text in Dari, English, or Cyrillic, ranging from political slogans to personal testimonies of loss.

Over the years, war rugs have been interpreted in various ways, as evidence of exploitation and problematic labor conditions, but also as expressions of resilience and creative survival in uncertain circumstances. Despite ongoing debates about their supposed meaning, war rugs remain unmistakably powerful records of historical documentation and the lived experience of Afghan people.

❋

Works Cited

“Afghan War Rugs.” MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art, 30 June 2025, mapacademy.io/article/afghan-war-rugs/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2026.

Cichosch, Katharina. “War on Rugs.” Schirn Magazin, 12 Dec. 2019, www.schirn.de/en/schirnmag/afghan-war-rugs-knitting-history-hannah-ryggen-tapestry-hannah-ryggen-2019-context-en/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2026.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. “Refugees Magazine Issue 108 (Afghanistan: The Unending Crisis) – The Biggest Caseload in the World.” 1 June 1997, UNHCR, https://www.unhcr.org/publications/refugees-magazine-issue-108-afghanistan-unending-crisis-biggest-caseload-world.

All images via The British Museum.